With the arrival of every new year, we might feel called or even be asked to consider what our lives might look like by the end of the year; in five years; or even in ten years.

Recently, when asked to describe my ideal life in approximately ten years time, I offered some genuine-yet-vague visions.

I hoped for a daily routine rich with making art and writing about art-making, people, and places: their peculiarities and gravitational pulls, among other things. In ten years, I envision a life-still-in-progress but with “making” at the center, and equal commitments to family, relationships, and the dogged pursuits of awe and fun.

Today and most likely in ten years time, these pursuits are driven by curiosity and a longing to connect with people and place; by vitamin-enriched cereal, percolated coffee, and the wrinkled fruits of aging, making up for the vitamins and self-assurance that cereal fails to provide.

About one month, half a conversation about a betta fish, and several episodes of The Crocodile Hunter later, I’m still sitting with visions of “life in ten years time.” When I linger with this question, I can’t help but also think of:

(1) living gloriously and with gusto, like Steve Irwin and other excitable characters

(2) moving slowly, like a betta fish, with grace and care but without carnivorous intent

My conception of Steve Irwin is based primarily on childhood memory and a recent foray into old episodes on YouTube — but upon returning to The Crocodile Hunter, I was instantly compelled by Steve’s concentrated humanness; his capacity to live in the meatiness of every moment. Steve wrangles crocodiles and hypes up his crewmates in the name of (1) conservation and (2) complementary-yet-cinematic missions, like “Search for a Super Croc”: a series of episodes documenting his crew’s search for “nine monster crocs.”

In any episode, Steve moves fast — and he must, in the face of saltwater crocodiles biologically wired to stop, drop, and “death roll” (a frequent refrain throughout the “Super Croc” episode: “no death roll, mates!!!”).

As I reflect on the purpose and pacing of my own life and the lives of people I admire, I can’t find anyone else who moves as quickly as Steve — and honestly, I can’t imagine moving through my own life so fast.

Speed and super crocs aside, I’m taken by the childlike glee with which Steve moved (ever so quickly) across mudbanks, swamps, and the backs of alligators. Of course, Steve and the producers of The Crocodile Hunter contended with cinematic constraints: namely, constructing the ebbs and flows of croc conservation into episodic stories and conveying the distinct character of Steve Irwin incarnate (and controversially-titled “national treasure,” per r/australia).

In many ways, The Crocodile Hunter — although technically a documentary series — feels and looks like a performance. Yet every time Steve yells something along the lines of “Crikey!” and makes frenzied eye contact with the camera before hopping on top of a reincarnated dinosaur, the performance convinces me (that I need to become a conversationist? tbd).

Ultimately, I can’t resist the gravitational pull of a person who loves what they’re doing, where they’re living, where they’re both standing (a swamp!) and moving toward (a super croc!). Even in the comparatively languid, midwestern town of Lansing, Michigan, I want to imbue my own life with Irwin-energy: with intent and intensity, wonder, and a commitment to be here and connect. This is a commitment to be here now. here. this.

moving slowly in the midwest

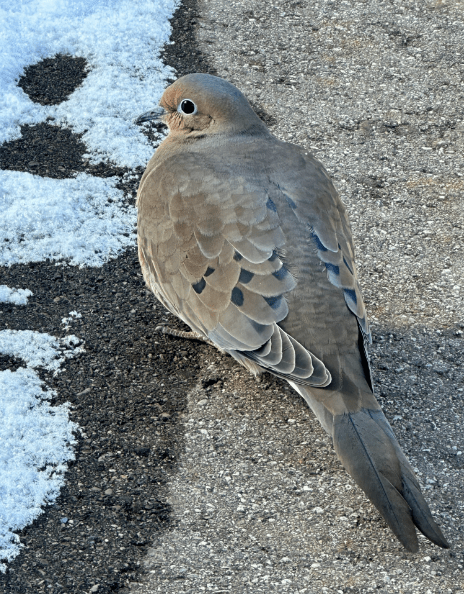

So here we are, here I am: with this avocado half or this eerily still bird or this sprightly older woman at Moriarty’s who just gifted me an entire box of leftover bar pizza after an evening of live jazz music. (Thank you, Candace)

Januarys in Moriarty’s — and, just outside the stained wooden door, Januarys in Lansing — are gritty and gray, and I can delight in both: particularly as I reflect on my prior residence in Philly, a city of gray buildings and gritty encounters.

Personified, Lansing could never catch a Super Croc, capture an international audience, or send a team of super-athletes to the Super Bowl. Yet there’s something just as gritty and sticky in her slowness, in her sometimes-almost-stillness, that Philly and other big-ol’-cities could never offer.

Despite or perhaps because of Lansing’s sloooooowed-down, small-town nature, I continue to commit myself to uncovering the people and pleasantries (P&P) of this midwestern city (and the state CAPITAL, at that!) via lunchtime walks and late-night roves into r/lansing, the designated subreddit for the Greater Lansing Community.

In Lansing, Reddit-endorsed perks include ample parking, cheap rent, and an active squirrel community, as well as local mysteries (like, what’s stored in the tall section of the Frandor Kroger?) and under-the-radar gatherings (like ecstatic dancing in the REO Town Marketplace), briefly heightening the city’s gently midwestern pacing.

Meandering back to new-year reflections and ten-year visions, these reflections on pacing — specifically, slower pacing — resonate with me, and I believe a growing segment of people in the spirit of slower living. As we contend with yearlong and lifelong realities of sociopolitical division, generative AI upturning our notions of “work” and creativity, climate change, and a host of other wicked problems, slowing down — and stepping back from it all, however briefly — feels really appealing.

slow slow slooooooow

Just this month, the hosts of the Critics at Large podcast covered the appropriately gradual rise of “slowness culture” in an episode titled “Can Slowness Save Us?”. Slowness might involve making contact with the ground via yoga mat or just rolling around on a carpet; stretching gently, speaking softly, Sabbath-ing on a Wednesday, and/or lingering in public spaces (a word in favor of the third place).

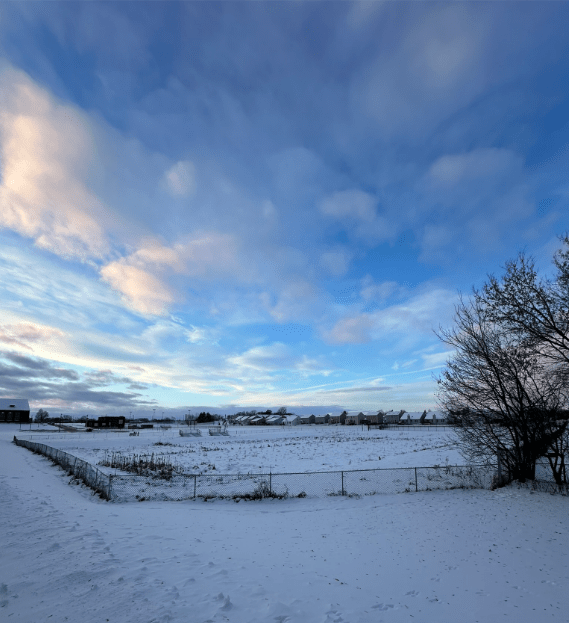

Within these gentle, intentional pursuits, perhaps we can create and/or perceive more time and space to rest, converse with fellow third-place occupants, or simply take in a snowy vista and briefly cosplay as a hunter-gatherer: scanning the horizon for a hefty rabbit and just enough kindling, all while fending off hunger and myopia.

Hunter-gatherer daydreams and generalized slowness are not cure-alls to our wicked problems, to the hurriedness of our individual lives, or means for self-improvement. And yet, especially in this hyper-optimistic month, I’m tempted to latch onto slowness as a salve, as a solve. Seemingly aware of this temptation, the critics-at-large ask: “Is too much being laid at the feet of slowness?”

Their response — and mine, as of now: perhaps, yes. When practiced intuitively and over time, I think slowness can save us: not from crocodiles, but certainly the chronic pressures and pulls of human life and the pain/stress/emptiness that speed can create and sustain.

Yet as I experience the temptation to lay everything at the feet of slowness, I’m compelled to ask: why am I, why are we so concerned with improvement via movement? Why are we so fixated on the quality, pace, and frequency of our movements, and their connection to the way our bodies look and feel and act in space?

I have no answers, but perhaps a better way to express the sentiment of these questions is to say: I don’t think the average bird — this pigeon, for instance — thinks much about controlling or gradating its movements; about slowing down, hustling, or jogging “at a good clip,” to borrow the phrasing of a former cross-country coach. Movement is not a desire so much as it is a biological impulse — like a super croc’s death roll — to navigate and conclude this scene and eventually this life, for now, heeding nature’s call and the occasional beckon of a pizza slice.

slower movements are having a moment?

The “movement-ication” of movement, as a podcast-able, Instagrammable, culturally recognizable thing, may make the pursuit of slowness feel more accessible, or at least, discussable. But, like almost any topic, too much dawdling on the subject might lead to overthinking. As Alexandra Schwartz, one of the critics-at-large, notes: “if you’re doing [slowness] ‘right,’ it’s not going to be noticed. It’s not something you’re going to be able to build a persona around” (timestamp: ~45 minutes).

I think movement — encompassing fast, slow, and every cadence in between — is better understood as an intrinsic, borderline-invisible expression of humanness. When we engage in movements that feel natural and enriching (maybe dancing, or bouncing, or plopping down in a public park), we’re honoring the opportunity, the inclination, the human right to sit or groove or just hang out with our “humanness,” as Schwartz puts it.

In an episode of the Invisibilia podcast about a tiny, aquatic, and questionably immortal creature called the hydra, reporter Lulu Miller and scientist Daniel Martinez discuss the relationship between motion and mortality. “Movement, to me, is the essence of life,” Daniel reflected. “The theme of life is movement.”

While I might generally favor a slower pace, I agree (as of this month — things can and will change) that movement is a major theme of human life. Perhaps the focus should be less on whether a given rate is “good” or “bad” for us, but instead honoring the variable, chaotic, wholly-untrendy nature of human movement.

As of late, I try to honor the desire to nest during winter, yet I look forward to contexts that call for a faster, livelier pace (such as televised crocodile encounters and recreational soccer games). Collectively, I can think of many instances in which we might benefit from moving slowly, lazily, or carefully: perhaps while trudging through a Midwestern blizzard for a pint of milk at Quality Dairy; sitting on a stoop on a summer evening, or sinking into a couch to catch up with an old friend.

I guess the undercurrent of these musings is attention: attending to our environments and bodies, what feels good and natural in a certain lighting — like a dancer, without moralizing or gatekeeping the decision to move fast, slow, whatever.

After listening to (one more) NPR podcast featuring dancer and choreographer Twyla Thorp, I think Twyla captures this notion well. She contends — with force and vitality, clearly fed by the fruits of aging — that we must “push against the reality” that threatens to constrain or limit our movements. In the midst of work, winter, children, assorted adult responsibilities, “we must create our own space,” Twyla asserts. “Otherwise, you know what? You will die.”

As the critics-at-large note, the accessibility of this space can vary, shaping individuals’ capacity to move freely and access their “humanness.” Here, for the sake of clarity, I’ll hone in on one of Twyla’s key reflections: that she couldn’t imagine her life without “moving and creating ritual in movement” (timestamp: ~9:40).

Ritual, to me, implies at least some degree of slowness or intention; of taking the moment (not an extra or additional moment, but just an unqualified moment) to soften a motion or think about the quality or purpose of a movement within the larger quilt of the day, the week, the month, a year — a decade.

By embracing opportunities for slowness, perhaps we gift ourselves and others a space to create ritual, to build something that sustains: a meal, a painting, a relationship. In this space, we are invited to linger and reflect; to consider how our pacing reflects our values, where we live, where we invest our finite life energy, and all the living, talking, loving, things, and stuff that come after the move.

Slowness might not save us, but I don’t think that’s the point. Lingering and considering the potential for ritual within any movement, in Lansing or in a swamp, fast or slow — I think that’s what does the saving.

Leave a comment